The Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) represents a pivotal period in Korean history, characterised by profound cultural development and transformation. Among the many artistic traditions that flourished during this era, najeonchilgi, or lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl, stands out as a symbol of Korea’s craftsmanship, aesthetic refinement, and philosophical ideals.

In the Early Joseon period, the consolidation of the Confucian state played a significant role in shaping the arts. While the influence of Goryeo Dynasty lacquer traditions persisted, there was a clear shift towards more restrained and elegant designs. Najeonchilgi from this period typically featured stylised motifs such as peonies, lotus flowers, and chrysanthemums, which reflected Confucian values of harmony, stability, and longevity. These motifs adhered to formal conventions, emphasising symmetry and balance, and embodying the period’s cultural ideals of order and refinement.

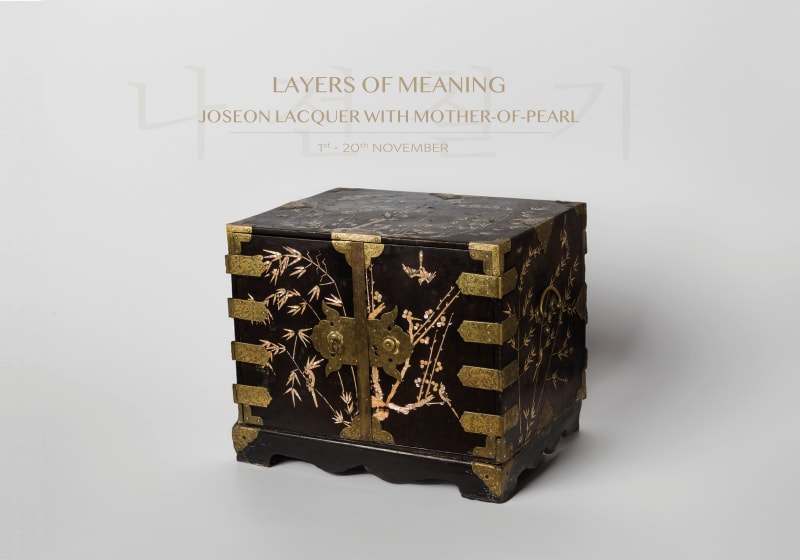

The Middle Joseon period was marked by political turmoil, particularly the Japanese invasions (1592–1598) and the Manchu invasions (1627, 1636). These traumatic events prompted a period of national reflection and recovery, mirrored in the arts. The social mood shifted towards resilience and introspection, with a renewed desire to forge a distinct national identity. During this period, the motifs of najeonchilgi became more naturalistic, reflecting indigenous Korean flora and fauna. Subjects like plum blossoms, bamboo, orchids, and grapes emerged alongside more dynamic flower- and-bird compositions. These motifs represented a deeper connection to nature and a desire for artistic expressions that were rooted in Korea’s own environment.

The Late Joseon period saw a flourishing of artistic production, driven by political stability. With the rise of a prosperous merchant class and increased foreign influence, the aesthetic focus of najeonchilgi expanded. New symbolic motifs such as bats, dragons, cranes, and the Ten Symbols of Longevity became popular, representing prosperity, longevity, and good fortune. The inclusion of geometric patterns and landscape motifs also became prominent, reflecting both the technical sophistication and the growing refinement of artisans. Larger pieces of mother-of-pearl were used to create bold, expressive patterns, and techniques such as hair-line engraving added intricate detail to the lacquered surfaces.

Throughout the Joseon Dynasty, najeonchilgi evolved in response to changing political and social landscapes, but it consistently served as a visual expression of the people’s ideals and aspirations. This exhibition offers a window into the development of najeonchilgi across these periods, highlighting the evolution of design, technique, and symbolism in this exceptional art form.